The Venturi Principle

Venturi Principle (Fig. 8)

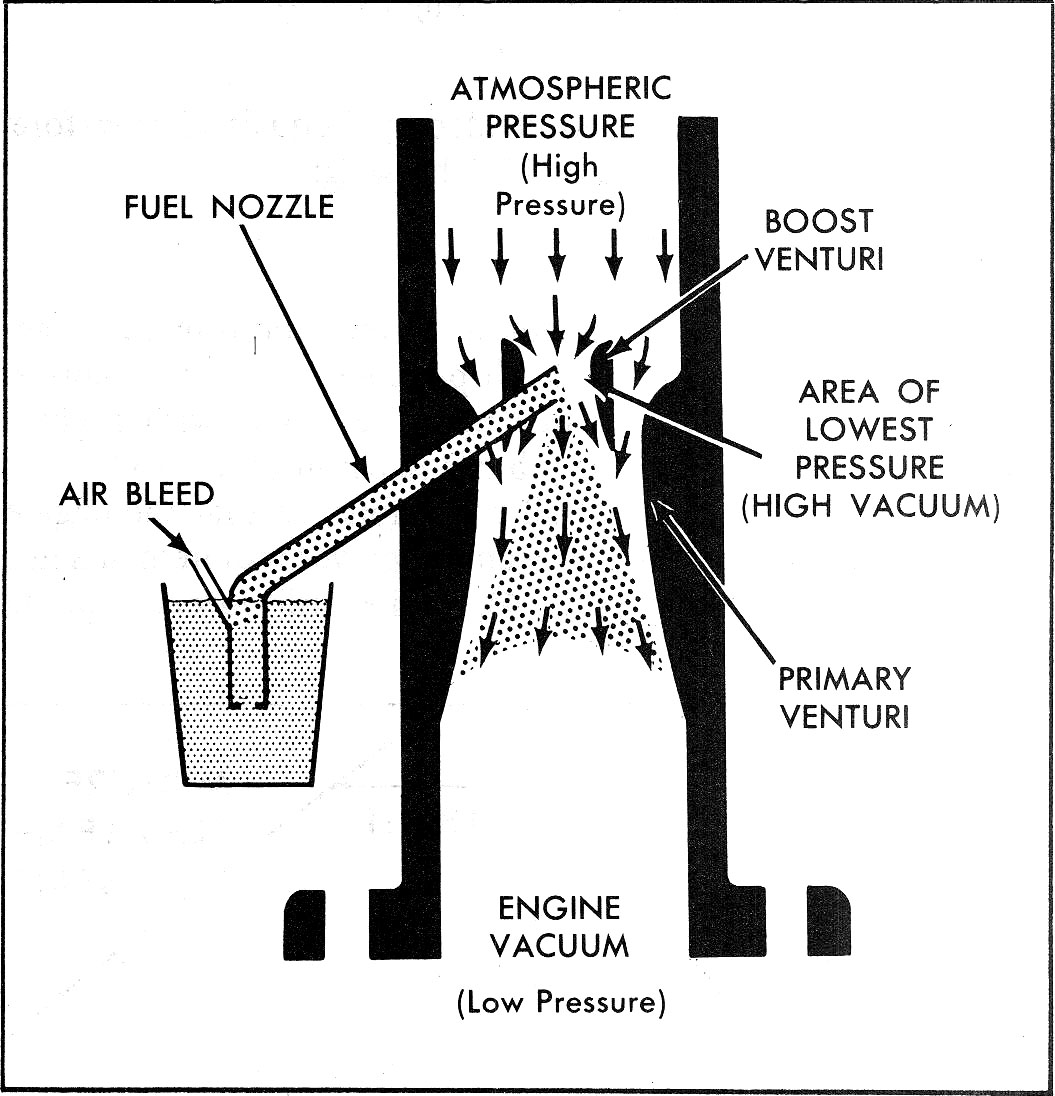

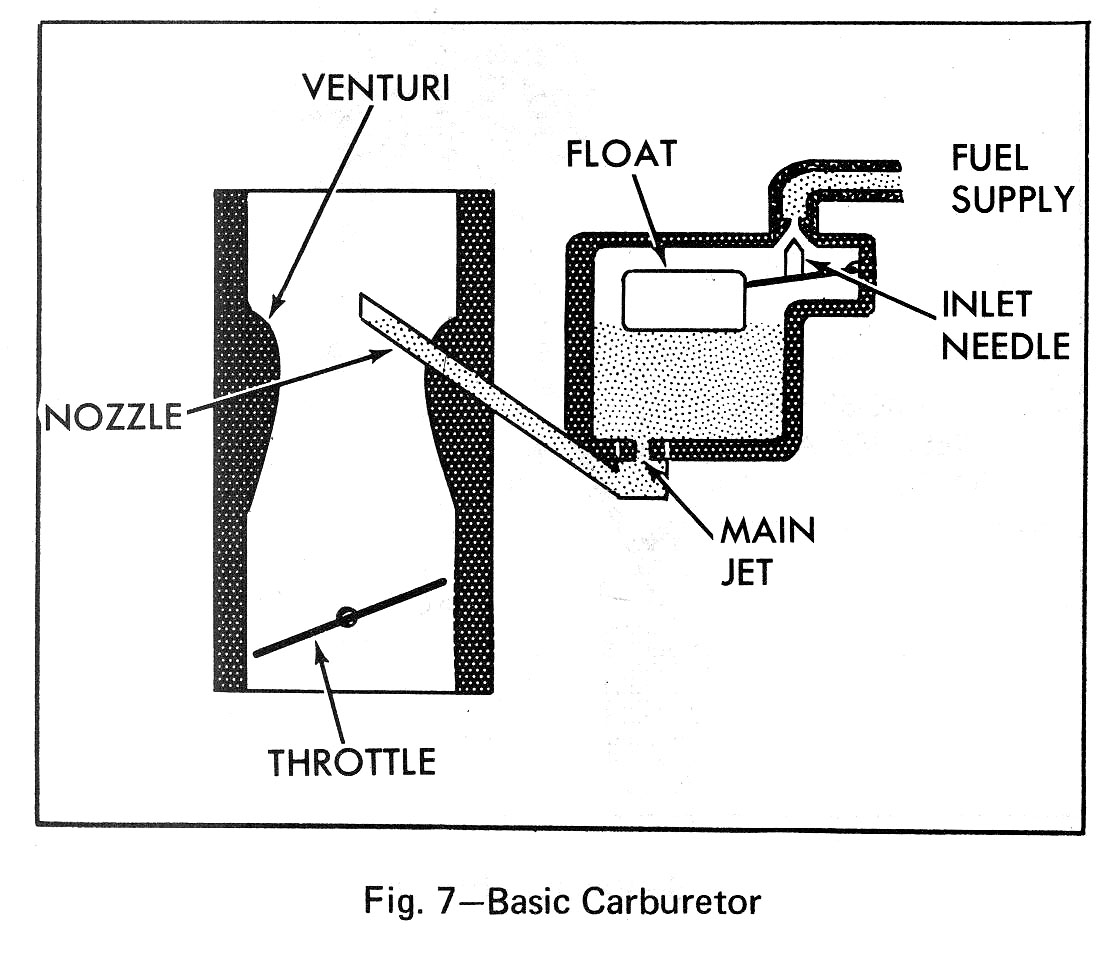

To obtain a greater pressure drop at the tip of the nozzle to cause the fuel to flow, the principle of increasing the air velocity to create a low pressure area is used. A device called the "venturi" is used to increase the air velocity and lower the pressure at the discharge nozzle. The increased pressure differential between that of the fuel bowl and at the carburetor throat increases fuel flow sufficiently, at a given air flow, so that the resulting air-fuel proportions result in a combustible mixture.

For example, a carburetor with a 1 1/2" pipe will supply the volume of air required for a given displacement engine. However, the pressure drop within the carburetor throat is insufficient to cause enough fuel to flow into the carburetor at the desired speed to create a combustible fuel mixture due to the large weight difference between air and gasoline. By necking down the inner diameter of the carburetor throat into a venturi, the air flow is forced to speed up at the restriction area, thus further reducing air pressure and increasing fuel flow proportionately to achieve the desired mixture.

To be most effective, the venturi must be designed for a certain curvature and length. The venturi design can be tailored to provide fuel flow under any condition of air flow. However, a small venturi may restrict high speed engine operation and a large venturi will not provide enough pressure differential for low speed operation. The production venturi size is usually a compromise to provide adequate low and high speed operation. The carburetor discharge nozzle is located in the center of the venturi throat to take advantage of the maximum pressure drop and promote atomization of the fuel. The large venturi, cast in the carburetor bore, is called the primary or main venturi.

Most carburetors use a primary and one or more boost venturis. The boost venturi is usually located over the primary with its discharge end in the low pressure area of the primary. The purpose of the boost venturi is to further lower the pressure at the nozzle. Additional boost venturis may be used for finer control of pressure drop but at high speed they tend to restrict air flow to the engine. Because actual venturi size is a compromise, two- and four-barrel carburetors are used where requirements are extreme.

A two-barrel carburetor allows use of smaller venturi for improved low speed operation yet gives relatively good high speed operation due to the larger throttle area provided by the two throttle valves.

The primary side of a four-barrel carburetor is designed much the same as the two-barrel carburetor with small venturi for low speed economy. The secondary side of a four-barrel carburetor uses large bores and venturi for extremely good high speed breathing. The secondary side of the four-barrel carburetor operates only at high degree primary throttle openings or when performance is required.

DISTRIBUTION

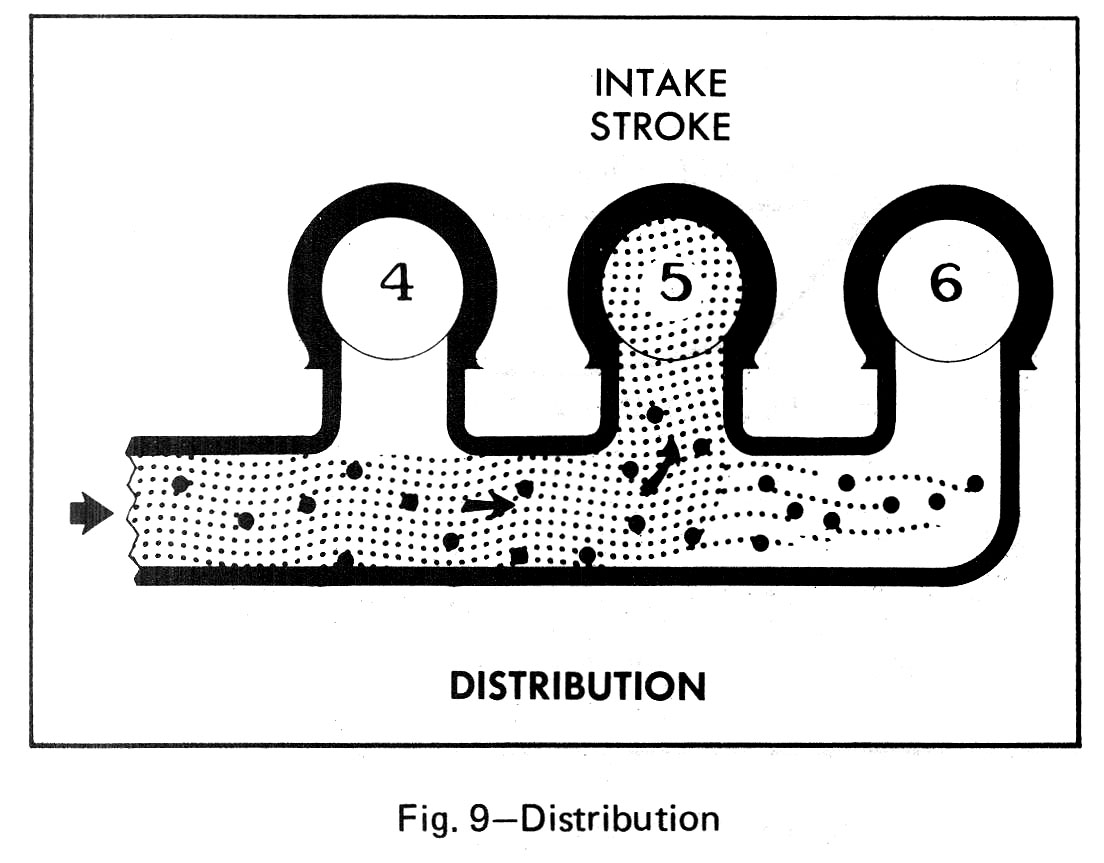

For good combustion and smooth engine operation, the air and fuel must be thoroughly and uniformly mixed, delivered in equal quantities to each cylinder and evenly distributed within the combustion chamber. Good distribution requires good vaporization. A gaseous mixture will travel much more easily around corners in the manifold and engine, while liquid particles, being relatively heavy, will try to continue in one direction and will hit the walls of the manifold or travel on to another cylinder. As an example, consider a six cylinder engine with the carburetor mounted at the center of the manifold. The mixture for cylinders 4, 5, and 6 will initially travel towards the rear of the engine. If #5 is on the intake stroke, the mixture will be drawn sharply around the corner to #5 at right angles to the original direction (Fig. 9). The large drops of gasoline won't make such a sharp turn and will continue in their path to the rear of the manifold, where they will probably be drawn into #6 on its intake stroke. Thus, #5 receives a leaner mixture and #6 receives a richer mixture than originally entered the manifold. To compensate for these problems, manifolds are tailored to the engines to minimize the sharp corners and provide as smooth a flow as possible.

The carburetor's principal job in distribution is to break up the fuel as finely as possible and furnish a uniformly vaporized mixture to the manifold.

next: Fuel-Air Requirements